It begins with some background on different percentages that have been identified as key to achieve tipping points. Young refers to those, as well, in in his article

The simplest formulation of critical mass theory maintains that small groups of regular individuals—that is, with the same amount of social power and resources as everyone else—can successfully initiate a change in social conventions. According to this view, the power of small groups comes not from their authority or wealth but from their commitment to the cause (14, 15).

Thus far, evidence for critical mass dynamics in changing social conventions has been limited to formal theoretical models and observations from qualitative studies. These studies have proposed a wide range of possible thresholds for the size of an effective critical mass, ranging from 10% of the population up to 40%. For instance, theoretical simulations of linguistic conventions have argued that a critical mass composed of 10% of the population is sufficient to overturn an established social equilibrium (14). By contrast, qualitative studies of gender conventions in corporate leadership roles have hypothesized that tipping points are only likely to emerge when a critical mass of 30% of the population is reached (3, 16). Related observational work on gender conventions (17) has built on this line of research, speculating that effective critical mass sizes are likely to be even higher, approaching 40% of the population. Despite the broad practical (18, 19) and scientific (1, 12) importance of understanding the dynamics of critical mass in collective behavior, it has not been possible to identify whether there are in fact tipping points in empirical systems because such a test requires the ability to independently vary the size of minority groups within an evolving system of social coordination.

Essentially, they wanted to set up their own test and used 196 subjects. Their finding was that 10% didn't cut it, but that close to 30%, or 25% could be enough to achieve the "critical mass" necessary to shift people's behavior and definitions from one way to another. "

Our results may suggest that in organizational contexts—where population boundaries are relatively well defined and there are clear expectations and rewards for social coordination among peers—the process of normative changes in social conventions may be well described by the dynamics of critical mass."

They consider possible implications and uses for that phenomenon, including the kind of social media influence that makes people concerned about manipulation:

Recent work on the 50 Cent Party in China (32, 33) has argued that the Chinese government has incentivized small groups of motivated individuals to anonymously infiltrate social media communities such as Weibo with the intention of subtly shifting the tone of the collective dialogue to focus on topics that celebrate national pride and distract from collective grievances (32). We anticipate that social media spaces of this kind will be an increasingly important setting for extending the findings of our study to understand the role of committed minorities in shifting social conventions.

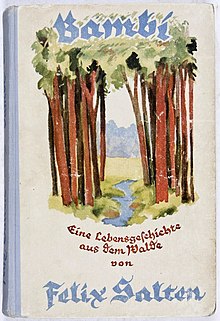

_Girl_in_mask.jpg/1280px-COVID-19_(Coronavirus)_Girl_in_mask.jpg) |

| photo from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/COVID-19_%28Coronavirus%29_Girl_in_mask.jpg/1280px-COVID-19_%28Coronavirus%29_Girl_in_mask.jpg |

So what's that got to do with masks? Quite a lot actually. The challenge in the United States and possibly other countries is the association with masks as threatening. I recall someone saying back in March that she felt "creeped out" by seeing a couple of Asian women in masks in a store. I didn't see any threat in that and pointed out that in Asian, it's quite normal. The irrational response, though, is deep-seated in one's expectations, and shifting that was and continues to be a challenge where masks are promoted and even mandated by policies intended to curb the spread of COVID19.

So we enter the realm of clear persuasion, and that brings us to a consideration of the master of persuasion, Robert B. Cialdini, the lead author on

Managing social norms for persuasive impact

On the one hand are descriptive norms

(sometimes called the norms of ‘‘is’’), which refer to what is commonly done,

and which motivate by providing evidence of what is likely to be effective

and adaptive action: By registering what most others are doing, one can

usually choose efficiently and well. On the other hand are injunctive norms

(sometimes called the norms of ‘‘ought’’), which refer to what is commonly

approved/disapproved, and which motivate by promising social rewards and

punishments. Thus, whereas descriptive norms are said to inform behaviour

via example, injunctive norms are said to enjoin it via informal sanctions.

The challenge for motivating mass mask wearing in the interest of public health here was twofold:

1. It represented a complete 180 degree turn from official statements put out by the likes of WHO and the CDC as late as April, which created problems of trust and consistency in perception.

2. It demanded adopting a kind of behavior that was completely alien and even suspect to the American culture, and demanding any requirement at all generates resistance in the name of individual rights in a country that has "Don't treat on me" rendered into its essential identity.

Generally, the influence campaign has been successful overall, from what I see, though I am in a state in which mask are required in stores and other indoor places by law.Most people will comply with law, o even when people fail to keep their masks on properly in a store, they will do so when reminded by a store employee.

However, getting them to voluntarily submit to something that is not required is another matter, and then you get into the gray area of demanding masks where they are not required or trying to shame people into or out of mask wearing in the name of science when it really is all done in the name of one's own comfort level.

What I mean by the latter is the extreme division I've seen about mask. Now some people think it's all about politics and will divide the mask camps in Republicans and Democrats. But that is as reductive and simplistic as it is false. I know plenty of conservative people who cling to masks as if they were as protective as foolproof vaccines and people who are not the least bit political who will say that the masks are useless and that they will not wear any (though the ones I know are not so pigheaded about it to still walk into a store that requires mask without one in the name of individual freedom).

So here's the question: what's going on with the tipping point? It seems clear that MSM and social media campaigns, not to mention doctor recommendations would have achieved enough critical mass to get everyone on board. Why is it not a resounding success?

Part of the answer likely lies in the Cialdini article:

For information campaigns to be

successful, their creators must recognise the distinct power of descriptive

and injunctive norms and must focus the target audience only on the type of

norm that is consistent with the goal. This is far from always the case. For

instance, there is an understandable but misguided tendency of public

officials to try to mobilise action against socially disapproved conduct by

depicting it as regrettably frequent, thereby inadvertently installing a

counterproductive descriptive norm in the minds of their audiences

The intended outcome of getting everyone to embrace masks is what is described in the conclusion of the Cialdini article:

It is possible to do so by conveying to recipients that the desired activity is widely performed and roundly approved, whereas the unwanted activity is relatively rare and roundly disapproved. Such a line of attack unites the power of two independent sources of normative motivation and can provide a highly successful approach to social influence.

But I think that there is yet another force at play: assumptions of risk/benefit ratios, as well as those who buy into wishful thinking even while claiming to be on the side of science. To illustrate, here's a tweet posted on July 19. 2020:

@DrKarlynB

In Whole Foods, they all crowd each other even if it’s completely unnecessary. It’s like they’ve forgotten that the WHOLE POINT of masks originally was to wear them when you COULDNT sociably distance. Instead, the masks are literally acting like a security blanket.

Dr. KarlynB hits the nail right on the head. The biggest mask advocates really do regard it as a perfect safeguard that enables them to do whatever they want without holding back. That shows a very poor understanding of science because all those masks most of us are wearing are clearly labeled as NOT MEDICAL GRADE and, at best, reduce the risk of transmission somewhat. What is that "somewhat" I refer to? I've seen no clear answer on that. I've seen the memes that 90% protection, but those are based purely on speculation and not on any hard data. In fact, you'd likely see that even those figures are linked to maintaining 6 feet of distance, which means you're not relying on mask alone.

Don't believe me? Would you believe the Mayo Clinic? Check out is wording on the mask recommendation here: It is careful to qualify that the face masks are effective only IN COMBINATION: See

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-mask/art-20485449

The only masks proven to cut down on the risk of contagion by better than 90% on their own are the ones reserved for medical workers and those developed especially for the people who want better protection than they can get from what is available to the public and who are willing to shell out some $50 or more for each reusable mask. See

https://sonoviatech.com/shop/

Coda: As for me, I 've worn a mask into the supermarket and post office since April -before it was mandated by state law. But I also do my best to avoid being in a crowds among others, including only using the outdoor ATM for the bank and avoiding visits to stores that can deliver what I want online without excessive charges.

_Girl_in_mask.jpg/1280px-COVID-19_(Coronavirus)_Girl_in_mask.jpg)