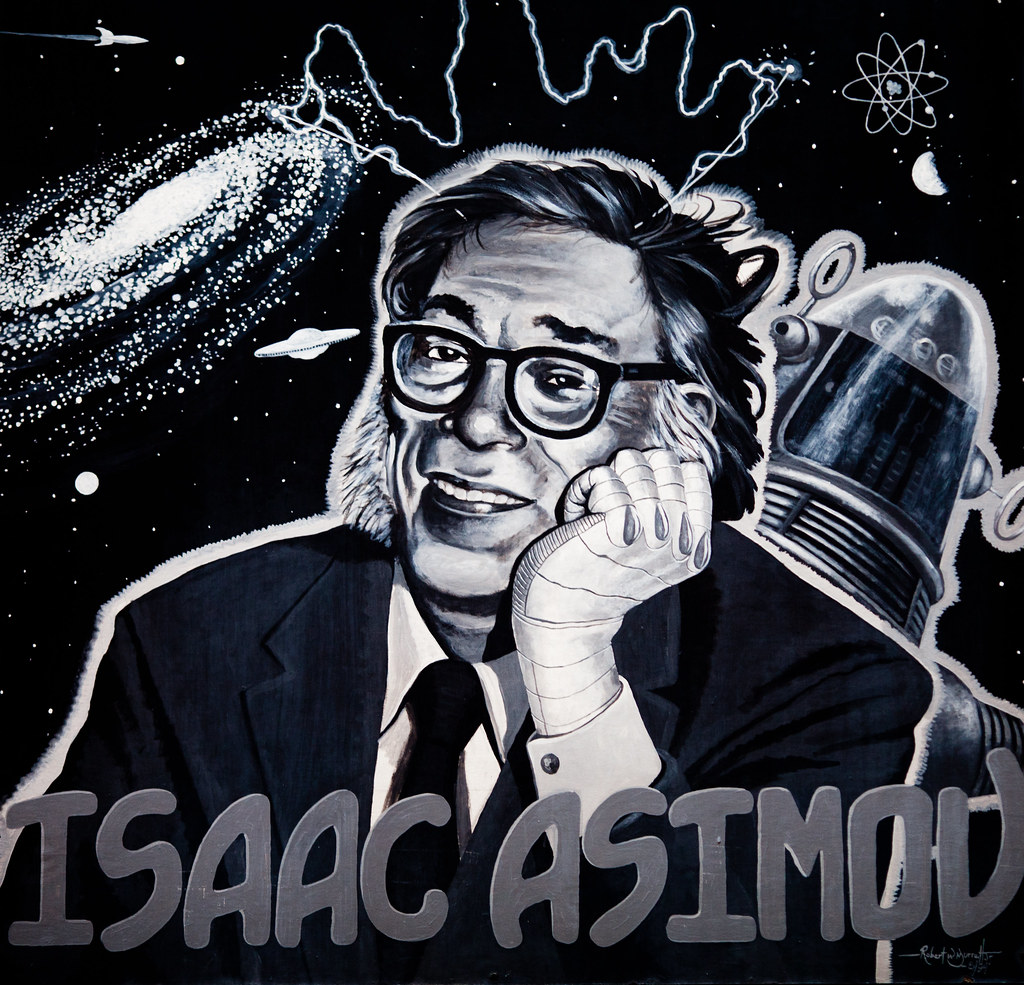

Clearly Isaac Asimov lived before "synergy" (now displaced by "collaboration") was buzz word. In 2014 MIT Technology Review ran "Isaac Asimov Asks, 'How Do People Get New Ideas?' and cited Asimov's 1959 essay on creativity.

|

| from https://c2.staticflickr.com/8/7380/12625238314_6794bf272c_b.jpg |

Like Woz, quoted in Susan Cain's Quiet and here, he does believe "isolation is required" to achieve creativity. His description of a creative mind also corresponds to how introverts operate: "His mind is shuffling his information at all times, even when he is not conscious of it."

What's interesting, though is his describing the intrusion of others as not being a problem due to distraction but to introducing self-consciousness that would impede progress: "For every new good idea you have, there are a hundred, ten thousand foolish ones, which you naturally do not care to display."

However, Asimov doesn't go so far as to say that you should shut yourself off from society altogether. He explains that interacting with others has other benefits for the mind

Yet that doesn't mean that he considers the group dynamics to lead directly to new creative insights. Instead they "educate the participants in facts and fact-combinations, in theories and vagrant thoughts." For the group to work in that way, he warns that the group has to not be at all censorious. He explains that even one person can poison the atmosphere in which all creative expression is unimpeded:

No two people exactly duplicate each other’s mental stores of items. One person may know A and not B, another may know B and not A, and either knowing A and B, both may get the idea—though not necessarily at once or even soon.

Furthermore, the information may not only be of individual items A and B, but even of combinations such as A-B, which in themselves are not significant. However, if one person mentions the unusual combination of A-B and another the unusual combination A-C, it may well be that the combination A-B-C, which neither has thought of separately, may yield an answer.

He also offers advice on capping the number of group members. Any more than five, he believes would be counter productive because of "the tension of waiting to speak, which can be very frustrating." But even more important than that is the question of expectation. In other words, one's official job should not be to what today is called "ideate."

If a single individual present is unsympathetic to the foolishness that would be bound to go on at such a session, the others would freeze. The unsympathetic individual may be a gold mine of information, but the harm he does will more than compensate for that. It seems necessary to me, then, that all people at a session be willing to sound foolish and listen to others sound foolish.

If a single individual present has a much greater reputation than the others, or is more articulate, or has a distinctly more commanding personality, he may well take over the conference and reduce the rest to little more than passive obedience. The individual may himself be extremely useful, but he might as well be put to work solo, for he is neutralizing the rest.

The way he puts it is this: "The great ideas of the ages have come from people who weren’t paid to have great ideas, but were paid to be teachers or patent clerks or petty officials, or were not paid at all." The ideas just came while they pursuing other things, which, he feels is important to remove a sense of obligation: "To feel guilty because one has not earned one’s salary because one has not had a great idea is the surest way, it seems to me, of making it certain that no great idea will come in the next time either."